[ad_2]

Source link

Through its visionary cinematography and costume design, Federico Fellini’s 1963 film masterfully blurs the lines between memory, reality and fantasy.

This feature is the first in our summer series, La Dolce Vita: A Celebration of Italian Screen Style, in partnership with Disaronno.

Asked to describe the anarchic ‘plot’ of what would turn out to be one of his greatest cinematic achievements – a towering, madcap, melancholy exploration of artistic endeavour, male ego and personal failing – writer/director Federico Fellini settled on a rather ambitious statement. He sought to depict, he said, the three different planes “on which our minds live: the past, the present, and the conditional – the realm of fantasy.”

You might say that when it comes to the costuming of these impish, dreamlike figures, fantasy is as much a factor as is any impetus toward realism. They are symbolic as much as they are corporeal, with protagonist Guido Anselmi (played by the dashing Marcello Mastroianni) an autobiographical stand-in for Fellini himself. Piero Gherardi was the man for the job: the costumer and set designer would become a second-time Academy Award winner for 8½ off the back of his 1960 win for La Dolce Vita.

For the insouciant elegance of Guido, a trim black suit is the uniform of choice. Guido dons Neapolitan-style tailoring in the form of this silk suit – some say it’s Brioni – along with a white cotton shirt, black tie and black-frame glasses. His suit is less angular and more rounded around the shoulders than traditional 1960s tailoring – not to mention paired with penny loafers to suggest a rather more bohemian, unconventional side to his character’s supposed professionalism. You can also see it in the character’s unusual choice of headwear – a rather incongruous, old-fashioned hat – which is remarked upon by other characters in the film.

Meanwhile, in contrast to the rather tidy black-clad Mastrioanni, the women of the film are peacocks, dressed in various degrees of surrealist adornment. Guido remains both tormented by and in thrall to the women of the film – Anouk Aimee is chic and miserable as Luisa, his long-suffering wife, disguising her malaise behind black wraparound sunglasses.

Guido’s mistress, Carla (Sandra Milo), wears only negligee, ostentatious white furs and heavy makeup – vulgarity writ large. But Claudia Cardinale plays an actress (who shares her first name) whom Guido casts as his ‘Ideal Woman’. She’s enigmatic and carefree, a beguiling and unknowable figure who can only exist in fantasy. “You’ll be dressed in white with your hair long, just the way you wear it,” Guido tells her, notably mentioning clothing.

But we never actually see this vision materialise; instead, Claudia is black-clad in their nocturnal foray through Rome, far from the innocent pastoral figure he seems to be idealising her as for his screen role. Her LBD drips with matching black feathers – not the only bird-like echo in the film, and reflecting the more stark reality: less dove, more raven. Indeed, the hatwear worn by women throughout the film is strikingly avian – no doubt a reflection of the symbolic importance of flying and birds to traditional Jungian dream interpretation.

It is ultimately Cardinale’s style which has the greatest import for 8½ because she is a figure of such projection and fantasy, the muse to an artist desperate for inspiration and a man who is spiritually and sexually conflicted. Failing to fall into the Madonna-mistress dichotomy, the playfulness of her clothing seeming to be either entirely in black or white feels ironic. There’s no objectivity in the way she is seen by Guido. And it’s that subjectivity which is the guiding principle of Fellini’s world of dreams.

To find out more about Disaronno’s 500-year anniversary* celebrations, visit disaronno.com

*1525: The legend of Disaronno begins.

Violent crime rates actually took a dive in 2024. Homicides, in particular, saw a significant decrease of 16% compared to the previous year.

It is understandable to feel scared when you face criminal charges, no matter the crime. It is normal to feel mixed emotions – confusion, stress, and uncertainty about the future. One big worry that you may consider is whether involving a lawyer is worth the investment.

The truth is, a criminal charge can affect your future in a big way — your job, your freedom, and even your family. Fortress Law Group says any charge you face, big or small, causes stress to you, your friends and your family, but it’s important to know that you don’t have to go through this alone.

That’s why you deserve to work with someone you can trust to represent you well.

If you face charges in a criminal matter, comprehending the role of a criminal defense lawyer becomes crucial. Your lawyer represents you in the complex legal system.

They will scrutinize the evidence presented against you, identify weaknesses in the prosecution’s case, and craft a defense theory in your favor. They may also work out plea bargains, represent you at hearings, argue your case, and ensure that your rights remain protected.

Legal experts can present you with all the diverse possibilities available so that you can make an informed decision about what step to take, especially with the most serious or grave offenses, such as crimes of sexual assault, sexual abuse, and rape, says sexual offenses lawyer Lee A. Koch.

You aim for the best possible outcome, which could include a lighter sentence, dropped charges, or being acquitted; this is the goal that a defense lawyer will strive to achieve.

Knowing how much legal representation would cost is important; criminal cases are hard enough as they are. When you employ a criminal defense lawyer, the charges you pay him may include consultation fees, hourly fees, and possible retainer fees.

With the complexities of the case, these fees can sometimes get quite high. Some lawyers might work on a flat-rate basis for certain services, whereas others operate under hourly rates for services provided regarding a case.

Court charges, expert witness fees, and even investigation costs typically require your payment. So discuss the topic of payment upfront with your lawyer to avoid unpleasant surprises.

Weighing the costs against the potential risks of self-representation will assist you in making a decision about getting a lawyer.

You may feel competent preparing your defense, but being your criminal lawyer might backfire. Complex laws and courtroom procedures may be difficult to understand without legal training. You may botch your case due to ignorance.

You may also miss deadlines or fail to acquire vital proof for your pleading, and the court may cling to that negative position. Self-represented defendants are often denigrated by jurors and judges, likely because they are unworthy candidates.

Emotionally charged situations can make objectivity difficult, which hurts the defense. Weighing the risks against the modest cost savings usually makes one reconsider self-defense.

Criminal cases require an expert attorney for success. An attorney’s familiarity with the intricacies of the legal system proves beneficial when handling complex laws and processes.

They will evaluate the case, identify its strengths and flaws, and develop a defense strategy for you. If an attorney is experienced enough, negotiators and prosecutors create working connections with said attorneys that may benefit the client during negotiations.

They can also emotionally support you and help you understand your rights and legal issues. In the end, paying an expert will provide you peace of mind and increase your chances of success.

The cost of hiring a criminal defense lawyer is another topic of consideration when discussing the potential costs. Allegations could be severe enough to disrupt your life for years, making them worthy of your immediate investment.

Consult the attorney’s experience, past wins, and ability to manage your situation’s specificity. An experienced lawyer might get you out of fines, jail time, and any criminal records.

Compare the price to the cost of representation, including the lawyer’s fees, and you may also consider the financial liabilities precipitated by a conviction. A criminal defense lawyer would protect you more than just your money—practically, your future.

Be sure to take the route that best suits your aims and situations.

This is the first of three pieces published in collaboration with Queer East Film Festival, whose Emerging Critics project brought together six writers for a programme of mentorship throughout the festival.

Qinghan Chen

This year, Queer East presents a more defiant stance to the public. I felt it within the first three minutes of Takeshi Kitano’s Kubi, the festival’s opening film. When a headless corpse suddenly appeared on screen, I covered my eyes and nearly screamed out loud. In the next two hours, heads were severed with the flash of blades; homoerotic scenes were folded into the political intrigue. I closed my eyes more than once, retreating into the darkness, anchoring myself emotionally. When a disfigured head was kicked off-screen, the film ended. I fully understood what curator Yi Wang had joked about in his opening introduction: if you feel uncomfortable, please close your eyes.

In the cinema, I never know whether each passing moment will shock or stun me. Moving images pour down like a waterfall, an overused metaphor for queer desire, yet they are still potent enough to shatter my boundaries. But I can choose to close my eyes. With this act, my attention shifts away from the images on screen and turns inward, toward my own body. As a result, I become more aware of my existence. It feels like my eyes are building a temporary shelter, guarding my perception and granting me respite. When I am ready, I can open my eyes and jump back into that fleeting in-between space between myself and the screen. Perhaps I could discover new interactions between films and space.

I experienced a perfect accident after traveling an hour and a half to reach the ESEA Community Centre, where the short film programme Counter Archives was held. The screening room is a narrow space with a skylight, loosely covered by a piece of black fabric. Due to British summer time, the lingering daylight disrupted the images on the screen, making them blurry and erratic. Yet this imperfection created a unique feeling for me.

When Lionel Worthing (Paul Mescal) and David White (Josh O’Connor) meet over the top of a piano in a Boston college bar, the spark between them is instant. One is a talented vocal student, the other a composition major preoccupied with recording and cataloguing the folk music of rural communities – their shared passion for song is what brings them into each other’s orbit, and the onset of the First World War is what cruelly divides them for the first time. While David goes off to fight, Lionel returns to his family’s farm in Kentucky, where the work is hard and honest. By the time they meet again, they’re both a little worse for wear. A sojourn to rural Maine to continue David’s folk recording project provides both with a new sense of purpose, and rekindles their tentative romance, but like all great ballads, there’s tragedy on the horizon.

Oliver Hermanus’ sixth feature takes him to North America for the first time, casting two bona fide heartthrobs: Paul Mescal and Josh O’Connor. When The History of Sound was announced in 2021 it set the internet ablaze, with many excited about the prospect of a tender gay romance starring two of the hottest young actors in the industry – but the resulting film is perhaps more restrained and delicate, sparing in its sexual content, for better or worse. In fact, there’s something even a little distant about the film, in which Lionel and David’s romance amounts to a few months across several years, and much of the focus is on its aftermath. The film is more concerned with how this pivotal moment in Lionel’s life changed everything about the person he would become.

Josh O’Connor, seemingly incapable of delivering a bad performance, is wonderful and tragic as David, charismatic and glib and fantastically handsome. Who wouldn’t fall in love with him, or the way his tired smile never seems to reach his eyes? It’s a pity there isn’t more of him, and Mescal opposite is perhaps a little lost as Lionel, despite his best efforts to deliver a serviceable American accent and the charming chemistry between them. There’s just something a little too interior about his performance – it’s difficult to buy that his relationship with David really is as significant as the film wants us to believe it is. It’s also a little unfortunate for Mescal that he’s outperformed by Chris Cooper as an older version of Lionel; he delivers a searing emotional monologue in the film’s final act which provides some much-needed resonance. But to Mescal’s credit, his singing sequences are quite beautiful, as are O’Connor’s, and the folk soundtrack evokes Inside Llewyn Davis in its soulfulness.

The film feels weighed down by some unnecessary sequences that don’t help to drive the story forward, occasionally forgetting that the crux of the film should be Lionel and David’s relationship and its long shadow; a sharper cut might prevent the film from sagging once the lovers part ways. While comparisons with Brokeback Mountain are inevitable among those with a limited understanding of queer cinema, The History of Sound has far more in common with Merchant Ivory – particularly The Remains of the Day and Maurice – in its pervasive melancholy and sense of profound regret at past inertia. It’s not repression that powers The History of Sound, but the tragedy of understanding something far too late to chase it. Its buttoned-up nature and chasteness might frustrate those hoping for a more salacious story, but Hermanus and writer Ben Shatuck (adapting from his own short story of the same name) have produced a unique and moving romance for those willing to listen.

To keep celebrating the craft of film, we have to rely on the support of our members. Join Club LWLies today and receive access to a host of benefits.

The Academy Awards may be a glitzy party with an arbitrary approach to dishing out Oscars but, within the circus, are moments of gravitas. László Nemes is the embodiment of gravitas. His debut feature, Son of Saul, is a relentless immersion in the quest of a Jewish prisoner whose job, in 1944, is to clear Auschwitz’s gas chambers of the dead.

Bodies – out of focus, naked and stacked high – are in Saul’s peripheral vision. This creates grief and empathy for a character who searches for reprise, despite the nightmarish horror all around. Seeing Nemes with his baby face and bullshit-free speech collecting the shiny Best Foreign Film gong is a positive omen for the future of this impressively serious Hungarian 39-year-old.

LWLies: How did you recreate the conditions of the extermination camps?

Nemes: The film takes place in and around one of the crematoriums of Auschwitz, so we found the right location and building. It had all the levels of the crematorium, from the attic to the ovens level to the lower levels – the underground undressing room and gas chamber, outside the court of the crematorium and the outside. Everything was in one place so you could have a continuous experience filming between the one level and the next.

And all the piles of bodies that you see in the background?

I’m not going to comment on that. This is the secret of the workshop. I know how we did it but it has to remain a sacred thing when we’re talking about the dead. I don’t want to disclose too much about that.

What are your thoughts on creative independence? Do you strive for it? If so, how?

It’s scary how little we are allowed, as filmmakers, to have our own worlds created because of people who want to second guess the market but actually don’t know more about the market than we do. They try to say we should make this film so it looks like another film, which already had success. But filmmaking is about taking risks. If a filmmaker doesn’t take risks then cinema is dying. You can see how a sort of very static mindset has taken over European filmmaking and worldwide filmmaking.

So how did you do it?

Just stick to your ambition, then you wait until you get lucky and hope that the project doesn’t die within you. I think I got lucky. When I was close to not realising it – actually not making this film happen – the Hungarian Film Fund was the only organisation willing to support this film. Had they not done this, it would have been impossible to do this film.

Did you come close to crying or did you cry at any point?

No. Inside, yes, I still am.

How close is the finished film to the vision you had before you made it?

Sixty per cent. I only think of the 40 per cent missing. I never think of the 60 per cent that I made happen.

What was your full ambition?

To have it the same but better.

Would that have been a technical change?

No, not technical. I’m the only one who knows but it just frustrates me. It’s not really an emotional change, it’s not the approach. It’s more the scope of it.

And that still haunts you?

Of course, that’s why I can’t watch the film, but I think in two years it’s going to be easier for me to watch it.

Did you make Son of Saul because it was an issue you were obsessed with?

Yeah.

Has making this film changed the nature of your obsession?

Yeah, it makes it a little bit easier to live with the thought of… I tried to communicate something that I had an intuition of, the experience of being a human in the midst of the extermination machine – something that hasn’t been communicated in cinema, the visceral experience of it. Not the external point of view, not the survival point of view, but something immersed in the reality of one human being with the limitations, the impossibility of knowing what’s going to happen. I wanted the imagination of the audience to recreate the experience of the camp.

Did you always… because I read that some of your family members…

People were killed in my family. It was not unusual for Jews to be killed. But it’s a very traumatic experience and I think it’s transmitted from generation to generation, in an almost genetic way. I wanted to make a film about that because people tend to consider the concentration camp as either something remote and abstract or historical, not really taking place here and now. Or in a very over-aestheticised fashion. I wanted to make it harder for other people to make films in the camp because it’s so easy to go there but it should be very hard to go there. You have to have the responsibility as a filmmaker to go there and talk about it. I wanted to bring the present of it, the here and now, and not this remote point of view.

Have your family seen the film?

My mother, my aunt, a few people. I made this for people who died in my family who have no trace of their existence apart from a few pictures. So many people died in terrible ways and they tried to erase even the fact that they existed by not even scattering their ashes. There’s something very… the destruction of people is something very… I’m very obsessed by it.

What’s next for you?

I have a project that takes place before the First World war; it’s the story of a young women in Budapest.

Have you written the script?

We have a script but it’s being rewritten and we are already working the preparation of the film.

Does this symbolise that you’re moving on from…

Yeah, I have to leave the subject. I don’t want to live in a crematorium forever.

Son of Saul is released 29 April.

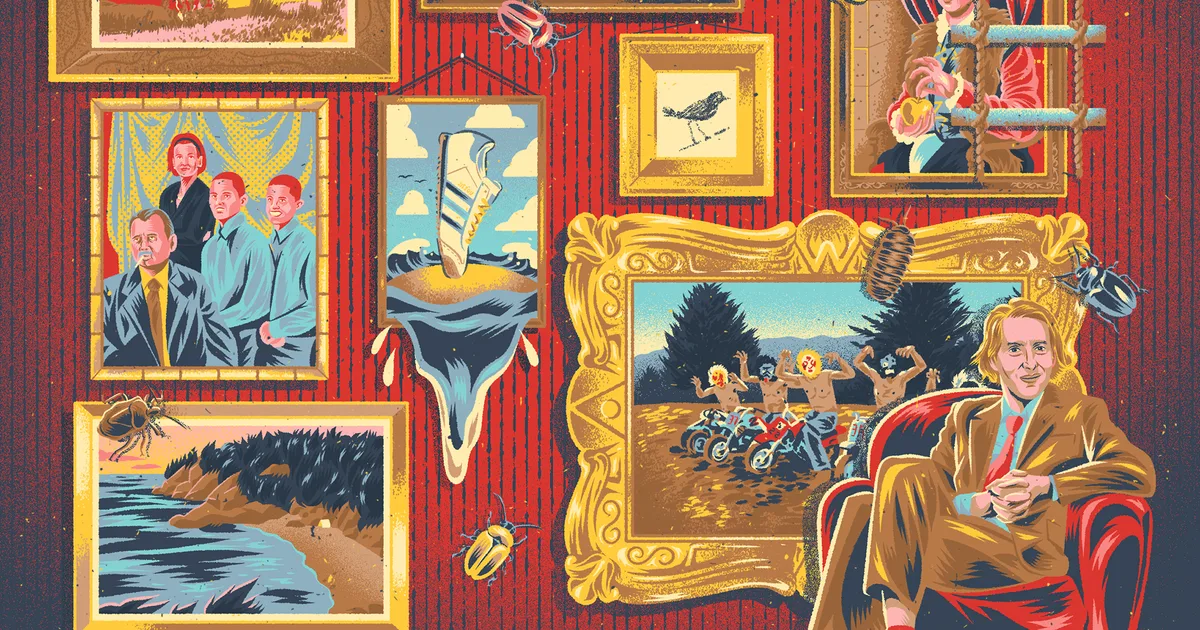

Like many of your films, The Phoenician Scheme features a lot of fine art, and I liked that you show all the paintings in the end credits. How do you decide on the art you use in your work?

Well, usually we’re making things for a movie and there may be some inspirations. We had these Russian forger brothers who worked on The Grand Budapest Hotel, and they did wonderful work, and they made a Klimt for us. They’ve also made other pictures for us: some cubist paintings that we had in the Henry Sugar movies we did, and they made me a Kandinsky that I have at home, all these fakes. And they’re wonderful fakes; they age them and they’re great.

In the case of this film, I had the notion that I would like to use the real thing which you never do on a movie because, if you say, ‘We’re going to use a Renoir,’ well, it means that there’s a group of people who come with that painting, and there are rules, and you can’t get a light too close to a Renoir, and the temperature of the room and the dust level in the room has to be maintained, so it becomes an obstacle. And of course people don’t really want to give you their Renoir. But our friend Jasper Sharp, who’s a curator, we went about the process and we found pieces that were not too far away, that we weren’t transporting across the globe, so we borrowed things, and we did have a team of different security and different gloved people looking after them, and it was fine. It takes a bit of effort, it has a bit of cost, but it was a great thing because you could feel it on the set. These pieces never just appeared, they arrived with some fanfare and with a bit of warning. ‘Everybody, here’s the real thing.’

The actors felt it. They were in the presence of these real pieces, and Zsa-zsa is a collector. He likes to own things. He’s a possessor. For instance, he gives his daughter this rosary, and we decided, ’Well, let’s use real diamonds, real emeralds, real rubies.’ We went to Cartier, and they made this piece for us, and they own it, but they loaned it to us. Every time Liesel is holding this in her hand, she’s holding however many thousands of euros of diamonds and rubies. It took Mia some time to feel comfortable, because it would break sometimes and it had to be repaired, but it was interesting and fun to do it that way, and I think they look better.

As someone who is so particular about aspect ratios and film formats in your films, I’m curious to know if there’s any film formats you’d be interested in working with. VistaVision is having a renaissance at the moment…

Well, I wanted to shoot on VistaVision.

Oh, no way!

We didn’t do it in the end because the logistics of it seemed to defeat us. At a certain point, we were just trying to make a certain budget work, but VistaVision was my first choice. What I actually am planning to do and just am doing some tests right now to determine is… so, I shoot on film. This movie is shot on 35 millimetre film, but as you know, 99% of the theatrical screenings in a cinema are a DCP, and the DCP is almost like you’re screening the negative. When you make a print, there’s grain in the print. So you have the grain from the negative and you have the grain from the print, and it’s not as sharp as the DCP. The DCP is as sharp as the original negative. I’ve watched my films as a DCP against the 35 millimetre film print, and the print is… it has the quality of film, and the film print is different. It has the magical thing of being a film print, but it doesn’t have the detail of the DCP. So what I’m going to try to do here is to make 70 millimetre prints from our 35 millimetre negative, which has been made into a 4K DCP, and see what that’s like because I think that that might be a kind of combination which hasn’t quite been done, and which might produce a very good film print.That’s a response to what you just said, which is not really an answer to your question.

No, no, you did answer the question! That’s fascinating to hear – and it’s interesting given how many films shot on digital are transferred to prints nowadays.

Well the idea is you just shoot on 65 the old way, 65 millimetre and you print on 70, but maybe using the digital intermediate at 4K might match something like that… but anyway, I guess we’ll see. I probably will not accomplish the same effect, but it’ll be some other thing in between.

And you always discover something from doing these experiments. Sometimes the things that you end up creating are not what you wanted to create, but they’re great anyway.

Yes. You’re hoping for the right accident.

What a lovely way of putting it! Speaking of fathers and daughters, your daughter has a small part in this film, and I was curious to know if this was her idea or your idea?

I think virtually every filmmaker’s daughter who’s ever been in one of their films, it was the daughter’s idea. [laughs] I was reluctant to put my daughter in a movie. But I’m glad I put her in because I love what she did.

Oh, I loved what she did! She understood completely her role.

She was very thoughtful about it and very focused, and it was a great experience for her, but you know, I don’t particularly think everybody needs to know that that’s who that is, but I guess anybody who’s interested will quickly figure that out. She loved doing it, though. I will say she wants to do it again.

The Phoenician Scheme is rooted in the idea of legacy, whether that’s familial legacy or artistic legacy, and what we leave behind, and what is left to the wider world when we die. Not to sound horribly morbid, but I’m curious, is that something that you end up thinking about a lot?

Let me think… I’ll say this: I have never made a movie where I would feel comfortable saying, ‘oh, that one was a mistake’. I’ve only made the movies I really wanted to make: my own movies. If somebody likes one and hates another, they’re still part of my family, and I just have to live with whatever they all are, how they are. I’ve always tried to treat them as a body of work to some degree, and even now we’re doing a thing with the Criterion Collection, they’re releasing my first 10 movies as a boxset. We’re doing a similar thing with the soundtracks, and we have the books about the films, and so on. So it’s something that I am conscious of and have been conscious of. I want these movies to all sit together as a set.

After the event of my death, I don’t really know if there’s really much point, but I do think about it in relation to my daughter. She’s going to be the one who is responsible for this stuff and I want it to all be in order for her. And I feel like so many people’s work, my own and all my collaborators – and there’s a lot of collaborators and a lot of artisans of so many kinds, all these actors, my co-writers and directors of photography, and production designers and painters and sculptors and puppet makers – all this work is contained in these movies. I feel it’s partly my job to look after them.

This ties into the exhibition that is happening at the Cinémathèque Français at the moment and that will be in London later in the year at the Design Museum, and making sure that this work isn’t lost to time like so much amazing art and so much amazing film history is.

You know, the exhibition wasn’t something I particularly wanted to do because I knew it was gonna take some time. It’s too much trouble! But I’ve been saving all this stuff all these years. I’ve been storing all these props and pictures and all these puppets, and so every now and then someone would want to show them. I kept saying, ‘I need to be older for this,’ but then when the Cinémathèque wanted to do it we decided it was time. The Cinémathèque to me is something that’s important to support, and the fact they wanted to do this, turned out to be a way for us to get everything organised for it to be an ongoing thing, so it’ll go to London, and then it has other destinations after that. I was dreading the process because I just want to work on my movies! But then in the course of it, working with a lot of people who I know well, and then Cinémathèque and the Design Museum, it turned out to be a good experience. I was there yesterday, in fact, because I had an official task to do, and there were all these kids and students in there, looking at our puppets… there was something rewarding about it.