This trend can also be traced in recent television series. In Apple TV+’s Severance, biocorp giant Lumon manufactures brain chips that allow users to “sever,” or switch on and off between, their work and personal lives. Grieving widower Mark Scout (Adam Scott) is compelled by the science as an opportunity to forget his wife’s passing for eight hours a day, rendering a version of himself that is not only a productive worker, but also lives relatively pain-free. The procedure is not without its down sides. The severance chip, activated by a spatial boundary, ultimately affects a temporal dissonance: office-bound ‘innies’ experience life as a continuous workday – “A weekend just happened? I don’t even feel like I left,” notes Britt Lower’s Helly R – while their ‘outies’ miss whole chunks of time. The show realizes this discrepancy in episodes that take place in “real time,” like in the first season’s whirlwind finale, or entirely within the warped linearity of the severed floor, as in the second season’s première, in which the time elapsed since the events of the first season is deliberately misrepresented to audiences and innies alike.

As with Invention and The Shrouds, the functionality of the tech at the root of Severance’s sci-fi conceit is echoed by the televisual technology that produces the show. Historically broken up by ads, episodes, and seasons, television – perhaps even more so than cinema – relies on time as its organizing principle and primary medium. “The major category of television” wrote theorist Mary Ann Doane in 1988, “is time.” The literally mind-bending technology of Severance, employed in the case of its protagonist to mitigate grief, splices time in the same mode as, well, a TV show.

In some ways, this reflexive pattern harkens back to the earliest days of moving image culture, when the technology’s newness often saw it put in conversation with modern anxieties over accident, disaster, or death. Early films like, for instance, the aforementioned comic trick film, The Big Swallow – in which a man approaches a camera photographing him and, in an act of irritation or amusement, eats it whole – played on the film apparatus’ ability to capture or depict nonexistence. Where the film might be assumed to end with a black screen, as the camera itself is swallowed, we’re instead shown the tripod and photographer disappearing into darkness, suggesting that film has somehow been able to capture an afterlife, even after its own demise.

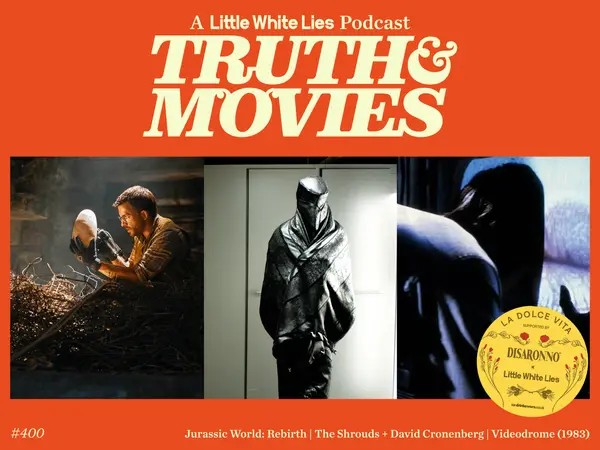

The effect of film’s ability to represent death has been the subject of much criticism and foundational theory. In 1951, French critic André Bazin suggested that film’s ability to capture and then repeat the unrepeatable moment of death – as in the documentary he was reviewing, Myriam Borsoutsky and Pierre Braunberger’s Bullfight – might both “desecrate” the finality of loss, while also rendering it “even more moving.” That ambivalence is then affirmed in these recent works where the sci-fi technology marshalled to counteract their characters’ grief does little more than complicate it. Mark Scout’s inability to recall the loss of his wife leads him to turn his back on her by the end of the second season. Invention’s Callie, after operating the healing machine, is moved to helpless tears rather than some deeper sense of peace or comprehension. The Shrouds ends ambiguously, with Karsh seeming to move on from his wife while, of course, continuing to see her everywhere.

But the lack of resolution is what makes these recent works such effective meditations on what moving image technology knows of – or owes to – death. Over the past few years, images of devastation have proliferated across mobile platforms, streamers, and big screens alike. Fears that such images might render viewers desensitized to grief or violence are counteracted by projects that explore visual mediums as tools for facing the fallout of death head on. If there is no treatment for grief, cinematically, it’s perhaps only because such treatment is necessarily ongoing, always unresolved. As technology continues to advance into realms some might call post-human, these recent works affirm that it can still remain a tool for exploring the most human thing: life and our responses to its ending. By inviting viewers to see film and television as a kind of “GriefTech,” these works underscore the blinding inevitability of loss without turning from it. That is: we only truly lose if we refuse to keep looking.