[ad_2]

Source link

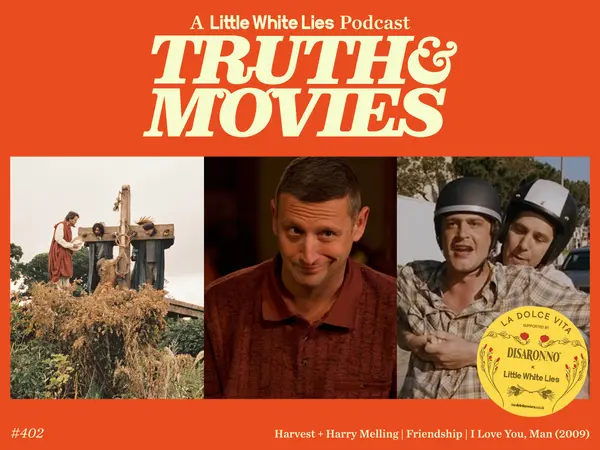

On Truth & Movies this week, the traditions of a village are forever changed in Harvest and its star Harry Melling spoke to us about the film. A man on the edge tries to befriend a neighbour in Friendship, and on Film club we revisit more attempts to forge connections as an adult in I Love You Man.

Joining host Leila Latif are Hannah Strong and Marshall Shaffer .

Truth & Movies is the podcast from the film experts at Little White Lies, where along with selected colleagues and friends, they discuss the latest movie releases. Truth & Movies has all your film needs covered, reviewing the latest releases big and small, talking to some of the most exciting filmmakers, keeping you across important industry news, and reassessing great films from days gone by with the Truth & Movies Film Club.

Email: truthandmovies@tcolondon.com

BlueSky and Instagram: @LWLies

Produced by TCO

In East Germany, where director Andreas Dresen grew up, Hilde and Hans Coppi were talked about with the kind of reverence normally reserved for saints. Members of a Communist German resistance group known as the Red Orchestra, which was working to aid the Soviet Union against the Nazis, Hilde and Hans were regarded more as symbols of heroism rather than real people who lived and died for their cause. From Hilde, With Love attempts to breathe life into the legend that Dresen was brought up with, but this handsomely crafted biopic is too staid to make a lasting impact.

Hilde, played with quiet resilience by Babylon Berlin’s Liv Lisa Fries, is picking strawberries when the Gestapo arrive to arrest her. The film begins as it goes on, with Hilde’s idyllic life with Hans (Johannes Hegemann), all kissing in sunlit gardens and harbouring Soviet spies, juxtaposed with the unmerciful reality of the Third Reich. As she languishes in prison, where she endures an agonising childbirth, flashbacks reveal her falling in with this group of young Communists for whom resistance is an adventure as well as a duty. For Hilde, however, it’s primarily an act of compassion; after hearing pleas from German POWs via illicit Soviet broadcasts she writes letters to their families, reassuring them that their sons and husbands are still alive. Discussion of politics is kept to a bare minimum.

Every one of these flashbacks seems to take place on the most gorgeous summer’s day imaginable. At times it’s rather too beautiful, a “Visit Germany” logo threatening to appear at the end of another sequence of cavorting by a lake or speeding through the countryside on a motorbike. A much more significant problem is that these flashbacks play out in nonchronological order for no clear reason. If it’s a vague stab at shaking up the biopic formula it doesn’t work; in practice it’s needlessly confusing, and that the romance between reserved, slightly prudish Hilde and the dashing Hans feels genuine is in spite of this narrative device. One particularly affecting montage features Hans teaching Hilde Morse code by tapping his finger on her body, whether on her naked back after sex or on her knee on the bus, a secret language of love that’s also an act of rebellion.

To the film’s credit none of the Nazi characters are so cartoonishly abhorrent as to divorce them from reality. Some within this system, such as a prison guard who helps Hilde appeal her sentence, even show some humanity, making their active participation in the régime all the more unsettling. In the current climate rejecting complacency in the face of fascism is a more pertinent message than ever, so while its ending is a gut-punch it’s a shame that From Hilde, With Love isn’t the formally bold, politically radical film that the Coppis deserve.

Making friends is hard. It’s even harder as an adult – while the media laments the ongoing “male loneliness epidemic”, many men and women are still reckoning with hard truths unveiled during the sudden solitude of the Covid pandemic. The destruction of third spaces, widening gaps in lifestyle exacerbated by lack of disposable income and increasingly unsociable working hours, and the increasing inability to detach ourselves from screens have culminated in a cross-generational crisis whereby plenty of adults – from eighteen to eighty – are realising they just…don’t have friends. The protagonist of Andrew DeYoung’s Friendship is one such case: Craig Waterman (Tim Robinson) is a marketing executive with a beautiful wife (Kate Mara), nice house and affable teenage son (Jack Dylan Grazer) but no social circle beyond the occupants of his house, who seem distant from him.

This all changes when the Watermans mistakenly receive a package intended for their new neighbour. Craig drops it off and meets Austin: a handsome, charismatic TV weatherman with a fully-realised sense of self. (Naturally he’s played by Paul Rudd.) Craig is instantly smitten, and despite being the new guy, it’s Austin who welcomes his neighbour into his life, showing him his fossil collection, sharing his love of punk music, and confiding that he secretly yearns to do the morning weather instead of occupying the evening slot. A bromance is born – Craig seems to come alive, a better husband and father while basking in Austin’s light. Then a tragic reality comes to light: Craig can’t hang.

This middle-aged middle American, who wants so desperately to be part of something, moves out of step with his peers. He’s assimilated a personality (liking Marvel movies, making crass jokes often at the expense of his wife) but can’t quite cover up the Travis Bickle-level entitled rot that lurks at his core. He parrots humanity but doesn’t exhibit it. There’s something deeply pathetic about Craig Waterman, but also something unfortunately true. This is Robinson’s great gift as a comedian – those familiar with his Netflix sketch show I Think You Should Leave will recognise his full-body-cringe-inducing style of comedy, which is, admittedly, something of an acquired taste. (Connor O’Malley, a similar cult breakout, delivers the film’s most baffling, brilliant non-sequitur during his short cameo in the film.) That’s not to say Friendship is punching down; Craig is an entirely ordinary villain who is absolutely convinced he’s the good guy. A nice guy, even. It’s evident from the film’s first scene, where – during her cancer survivors support group – he expresses confusion when his wife admits she hasn’t orgasmed since before treatment. “Plenty of orgasms over here!” he declares cheerily.

The same wildcard energy that made Robinson’s sketch series a cult classic is threaded through Friendship (DeYoung wrote the part with Robinson in mind). There’s a feeling that anything could happen at any moment, a strange pedestrian volatility to Craig that makes him just as likely to stew silently as to blow up in spectacular fashion, and the off-kilter sensation of something being not quite right is exacerbated by Keegan DeWitt’s oscillating score, which ramps up the tension with choral arrangements more typical of a horror film than a comedy. But Friendship arguably is a horror movie, evident in more than just its score and high wire tension between characters. The excruciating act of being vulnerable with another human being and the sweaty discomfort of realising a new friend is a bit off are mundane but relatable terrors, after all.

This feature is the fourth in our summer series, La Dolce Vita: A Celebration of Italian Screen Style, in partnership with Disaronno.

For all of the luxury it displays, the vitality in I Am Love comes from a more egalitarian source. Director Luca Guadagnino sets up a milieu where the ceilings are high and the catering costs are higher, where soup is served from silver tureens and the men are dressed by Fendi. Then, he spins the meaning of these aesthetic choices as the force of desire prompts his leading lady to take flight from it all.

Having developed the film with Guadagnino for 11 years, Tilda Swinton gives herself over to a sexual awakening that leaves her character, Emma, permanently unbuttoned from the costume of a previously well-worn life. Her erotic transformation takes place in a rural setting, amidst rolling hills, miles (literally and spiritually) from the lonely, opulent rooms that she usually occupies as a Recchio woman.

Emma is a Russian émigré who long ago sublimated her origins (and name) by marrying into an aristocratic Milanese family. As a wife and mother of three, Emma glides through her social and household responsibilities. She is a warm, self-possessed presence saying little during the dinners that mark one occasion after another. Visually she looks the part (dressed in Jil Sander by costume designer Antonella Cannarozzi) as she silently basks in her chief pleasure: food.

Yorick Le Saux’s golden-hued cinematography cleaves to the sensual digressions happening in plain sight even if they go unnoticed by a family preoccupied by its matters of the day. At a lunch with her glamorous mother-in-law, Allegra (Marisa Berenson), the conversation turns to whether Emma’s son Edo will marry his girlfriend. Both Emma and the camera are overcome by the indecent pinkness of a plump prawn that has just been delivered to the table. Le Saux’s close-up on Emma as she eats is intimacy incarnate.This dish has been cooked by Antonio (Edoardo Gabbriellini), a friend of Edo’s. The two young men plan to open a restaurant together in San Remo on the Italian Riviera.

From the moment that Emma sees Antonio – prepping tiny perfect morsels clad in chef’s whites – something within is shocked to life. Swinton performs a woman ground to a halt by a causal everyday encounter. Seconds later, Edo is there, missing the significance, missing the rupture, because his mother is a contained person whose interior revelations do not scan in an environment built for big statements.

Emma visits San Remo, full of unformed hopes, and ends up shoplifting a book called Atelier Simultane about another Russian émigré to France, the artist Sonia Delauney. This book, with its colour-splashed cover, is a talisman for all that she is about to experience. Cannarozzi’s costumes veer into a new palette, as oranges and reds clothe Emma’s lower half. Undressing is established as a motif.

Firstly, the camera spies on Antonio peeling off jeans in a hidden corner of a garden. Later, he disrobes Emma, tenderly undoing and setting aside jewellery before moving onto items of clothing. She will never dress the same way again and when they make love outside witnessed by flowers and insects, the only costuming is nature’s finery.

To find out more about Disaronno’s 500-year anniversary* celebrations, visit disaronno.com

*1525: The legend of Disaronno begins.

A review of Die My Love by Lynne Ramsay, which premiered in the Cannes Film Festival competition. Sadly, the film was a major disappointment. #Cannes2025

Source link

In hindsight, it is not surprising that the film’s nostalgic rendition of 1962 Hong Kong left such an indelible influence on an entire generation of cineastes. In the 2000s, Wong’s formal and narrative restraint set him apart from the increasingly grandiose cinematic ambitions of both Chinese and Hollywood studios. During this period, his peers like Ang Lee and Zhang Yimou choreographed complex fight scenes on picturesque vistas, interspersed with charged moments of intense melodrama. Wong resisted any temptations towards manufacturing maximalist spectacles. Even compared to other works in his oeuvre, In the Mood for Love is noticeably lacking in kinetic frenzies of violence or bursts of passionate intimacy. Instead, the film consists of long takes where characters, no more than one or two at a time, appear in the shot: writing, eating or sitting in plumes of cigarette smoke. In close-ups, yearning stares and brief moments of physical contact are in full focus. In the wide shot, lonesome figures walk away into the distance.

Of course, the film’s lasting legacy is more than just a mood board reference. At the turn-of-the-century, Wong’s magnum opus exists in contradiction to the promises of a new age. As the internet instantaneously connected billions of users around the globe, In the Mood for Love realized an interpersonal connection that transcended the framework of forums, chat rooms or video calls. For 25 years, generations of viewers raised in cyberspace continue to resonate with a deceptively simple narrative of a love affair that never comes to fruition. In the wake of unfettered economic globalization and the explosion of WiFi access around the world, Wong swam against the tides of digital excess. Except for a few phone calls and a telegram, signs of modern technology are absent from the film. By placing us in the past, divorced from our connections to the distractions of the present moment, Wong mines for the raw essence of a feeling.

The protagonists never get to unleash their desires on screen. In the hands of another filmmaker, Leung and Cheung would’ve likely been directed to throw themselves into each other’s arms, undressing in a steamy climax to relieve the 90 minutes of simmering sexual tension. Against all conventions and instincts, Wong instead pulls his two star-crossed lovers apart. There is no scandalous affair, just a fleeting slip into a fantasy that never truly plays out. With the film’s conclusion in mind, all the instances of controlled affection, the silent stares, the late-night writing sessions and the tame re-enactments of adultery feel even more erotic. The couple don’t end up riding off into the sunset together, but the time they shared as neighbors has left a seismic impact on their lives. Like idealized memories that stray further from the truth each passing day, each of Wong’s images revel in the saturated shadows of a nostalgic mirage.

In the Mood for Love clearly bears an important personal meaning for its director. What was probably intended as a love letter to a bygone era of Hong Kong’s history, a construction of childhood scenes where gossiping family members played Mahjong all night long, has now mutated into a mournful treatise to luxuriate in fading pasts. Whether it is a person, a place, or a memory, every frame of Wong’s masterwork allows viewers to get lost in their own sinkhole of longing. Recent box office and critical hits like the Daniels’ Everything Everywhere All at Once or Celine Song’s Past Lives are evidence that Wong’s impulse for nostalgia remains as widespread as ever. Though the former is far more direct in its homage to Wong’s film, both grapple with visions of what could’ve been. A vivid recall of fond memories and the invention of alternative futures might be our best recourse in dealing with an overstimulating, and overbearing present.

In The Mood For Love + In the Mood for Love 2001 will screen at venues across New York and London this summer.

There’s something about film noir that never loses its edge, especially for older adults who first watched those shadow-soaked tales, crisp dialogue, and twist-filled plots. Even now, many seniors return to black-and-white stories about crime, passion, and betrayal.

Whether they are unwinding at home or meeting friends for movie nights in assisted living communities, film noir still sparks lively chats, stirs emotion, and creates comfort. It offers more than memory; it preserves a bridge to a time when a movie could captivate without a single splash of color. That recollection alone can brighten an ordinary afternoon.

Film noir stands apart thanks to storytelling that is raw, candid, and frequently unpredictable. For seniors, these narratives remain current because they refuse to gloss over life’s shadows. Rather than neat conclusions, film noir often leaves viewers pondering the aftermath. Imperfect leads and hard choices mirror reality in ways that still hit home.

Older audiences respect that these films skip the sugarcoating and instead probe the deep feelings people wrestle with—love, grief, regret, and hope—inside an absorbing, suspense-driven plot. Each twist feels like a new discovery, even on the tenth viewing.

Watching film noir can feel like opening a well-worn time capsule. The music, clothes, cars, and neon streets summon vivid memories of another age. Many seniors came of age during or soon after the genre’s golden years, so revisiting these movies unleashes a strong rush of nostalgia. Recognizable faces—Humphrey Bogart, Barbara Stanwyck, Robert Mitchum—seem like long-time companions.

These films do more than entertain; they carry viewers back to the first time they saw them, whether in a crowded theater downtown or on a television with family. They recall popcorn aromas, marquee lights, and the thrill of neighborhood premieres.

Another hallmark of film noir is its razor-sharp dialogue. The lines crackle with wit, subtext, and flair. Seniors enjoy hearing characters speak decisively, using each word with intent. There’s a confidence and clarity in the way detectives, dames, and villains talk that still resonates.

Those quick exchanges offer sheer amusement yet also give the brain a pleasant workout, urging viewers to track each hint, secret, and double-cross woven through smoke-filled bars and rain-slick alleys.

Many modern movies bombard audiences with rapid cuts, booming sound, and layers of digital spectacle. Film noir, by contrast, moves with deliberate calm. It invites the audience to settle in, watch shadows shift, and allow the plot to breathe.

Seniors often welcome that measured cadence, where characters pause to think, and scenes linger long enough to absorb mood. It provides a quiet respite from today’s sensory overload and recalls a period when solid storytelling ruled the screen.

Film noir endures for seniors not only because of the era in which it was produced but because of the emotions it still evokes. With iconic characters, polished dialogue, and authentic emotional weight, the genre remains as compelling today as when it first emerged. In every dance of shadow on silver, there is a timeless allure that keeps drawing older adults back to these unforgettable stories.