That Was My Review of…..Reflection in a Dead Diamond

In 1988, Alex Cox introduced films broadcast on BBC with a segment called Moviedrome. When talking about Diva (1981), he said, “It’s the sort of film that American movie critics like very much because it’s big on style, short on substance, and in French. It’s the kind of film that gets called scintillating or fabulous frothy fun.” He concluded by saying that “it features musical selections from the noted opera, La Wally, un des mes favoris.” I had a recording of the film and that introduction for a long time, and I thought about it after watching Reflection in a Dead Diamond. The first reflection one makes is that American critics have changed significantly since then.

Reflection in a Dead Diamond (Reflet dans un diamant mort) is the fourth feature film directed by Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani. I stress the word directed since their films seriously focus on the cinematic aspects of the medium, which is all too rare nowadays. The film had its world premiere in the Berlinale Competition. It was the couple’s first film in a major competition after their previous two films were premiered at Locarno in the Piazza Grande strand. If I have been hiding behind the statement that favourite films are the most difficult to describe, this one tops them all. Even discussing the beginning and end is perilous when describing this diamond-fashioned narrative.

Early on, we see the elderly John Diman (Fabio Testi) at a beach on the French Riviera. He watches a girl from a distance. Suddenly, her diamond nipple ring sparkles in the sunlight and seems to trigger a memory in John’s mind that looks suspiciously like a movie ending with the young John (Yannick Renier) on a yacht with a girl and a box of diamonds. Then, some closing credits appear, saying, “C’était Reflet dans un diamant mort”. That text also serves as the opening credits of the film we are watching. What conspires in the remainder of the film is open to interpretation, and anyone looking for a straightforward narrative would be better off watching Mission Impossible (1996).

“It’s been said about my work that the search for style has often resulted in a want of feeling. However I’d put it another way, I’d say that style is feeling, in its most elegant and economic expression.” -Clive Langham

During the interview with the directors, they described how they built the story with three narrative lines in different colours. While sticking with the term story, they also stressed that they wanted to tell it with cinematographic means rather than dialogue. Hélène Cattet clearly stated that there is no contrast between the form and the content but that it’s one thing. It is similar to how the Clive Langham quote in Alain Resnais’ and writer David Mercer’s Providence (1977) brushes off the dichotomy between style and feelings. In that film, Clive, an author, makes up a narrative containing family members, but he constantly loses control over it.

Diamonds are Not Forever

The most ordinary way to describe the film would be that the ageing John looks back on his former life as a spy at a time when the Côte d’Azur was still a glamorous place rather than the tacky surroundings that greet attendants at the Cannes Film Festival nowadays. However, the film never clarifies whether we witness memories, fantasies, dreams, or all of them mixed up. It is no coincidence that the word diamond appears in the title since it mirrors the film’s complex structure. The usage of the word clarifies might be a tad unjust since the film’s various facets are never muddled or unclear, but how those elements fit together is a different story.

The directors have pointed to influences like the Eurospy films of the sixties, which tried to compete with the actual James Bond films but with a fraction of their budget. It is not difficult to spot references to Diabolik (1968), for instance. Regarding the structure, Satoshi Kon was mentioned with his kind of 3D narrative. The constant playfulness made me think about the films of Raoul Ruiz, not only Le Temps retrouvé (1999) but also the ones that toy with clichés and where characters suddenly do the most unexpected things. Another film that came to my mind was Ruben Brandt: Collector, with its irreverent and mischievous references to everything from Infanta Margarita in a Blue Dress to Pulp Fiction.

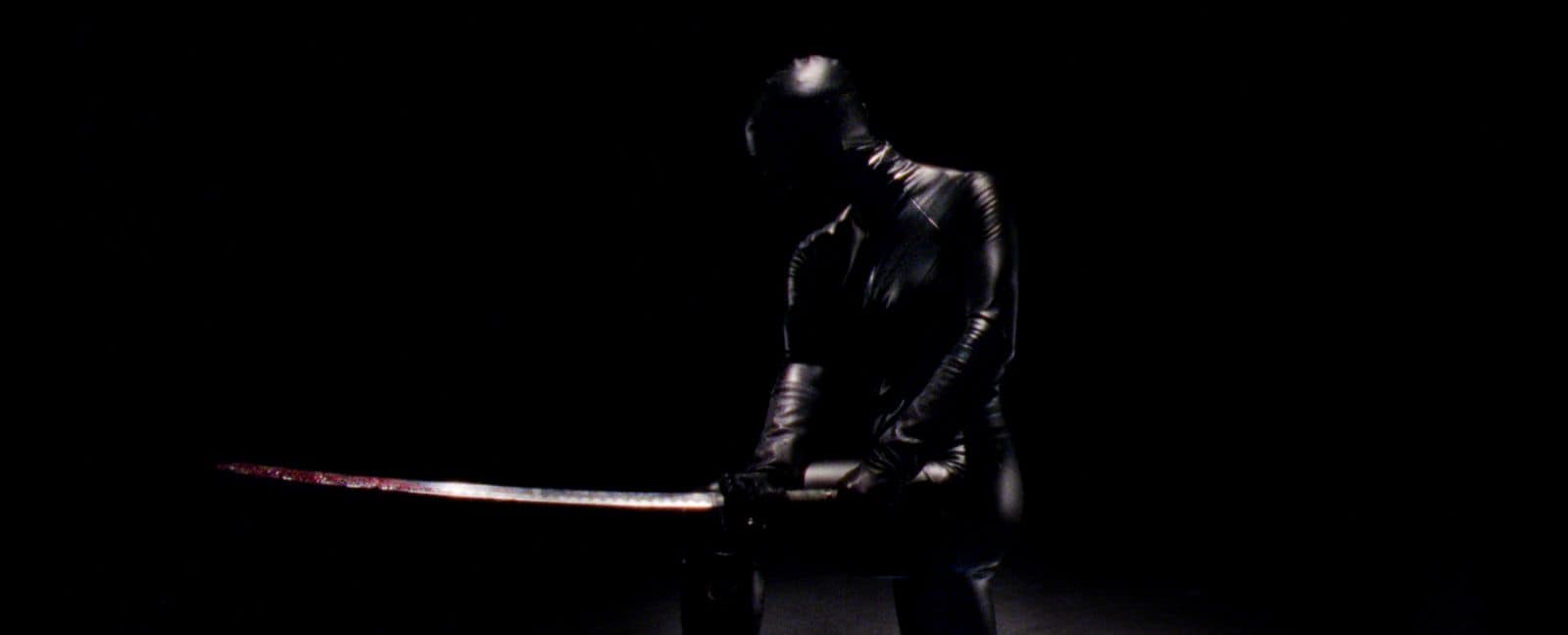

In a pivotal scene, young John undergoes a briefing where he learns about the opponents he is about to face. Among them are Serpentik, whom we encounter several times in different shapes and forms (and actresses), but the most dangerous is Kinetik. What makes him so dangerous is that he hypnotises his victims to make them believe that they are in a film. The spell only ends when they see the word fin, marking the end. This is a perfect metaphor for the structure of the film. Maybe parts or all of John’s story drive from this state of consciousness. Also, isn’t this the perfect way to describe what filmmakers wish to achieve with their audience?

The implications are numerous, and in my mind, this is the core of Reflection in a Dead Diamond. The fractured but beautiful illusion might refer to cinema itself. The Kinetik character alone would warrant a thesis or two. Going back to the beginning (or end) of this review, Alex Cox’s notion about style contra substance, which might have been said in jest, is shattered here into a myriad of crystal-clear diamond facets. His mention of the Diva score is interesting because Cattet and Forzani use not only the same piece of music but also the exact same recording used in Beineix’s film. One giveaway is an introduction that only exists in this version.

If my description of Reflection in a Dead Diamond makes it sound academic, nothing could be further from the truth. This is not only the directors’ most accomplished film to date but also one of the most thrilling, beautiful, sexy and bewildering works you will likely watch this year. It is indeed “scintillating and fabulous frothy fun.” I wouldn’t mind if I was hypnotised by Kinetik and had to live inside this film for a long time.

Seen in the Berlinale Competition, where it inexplicably walked away empty-handed.

Reflection in a Dead Diamond

Director:

Hélène Cattet, Bruno Forzani.

Date Created:

2025-04-26 19:58

Pros

- Intelligent

- Endlessly entertaining

- Cinematography

- Editing

Cons

- Eventually, the film ends.