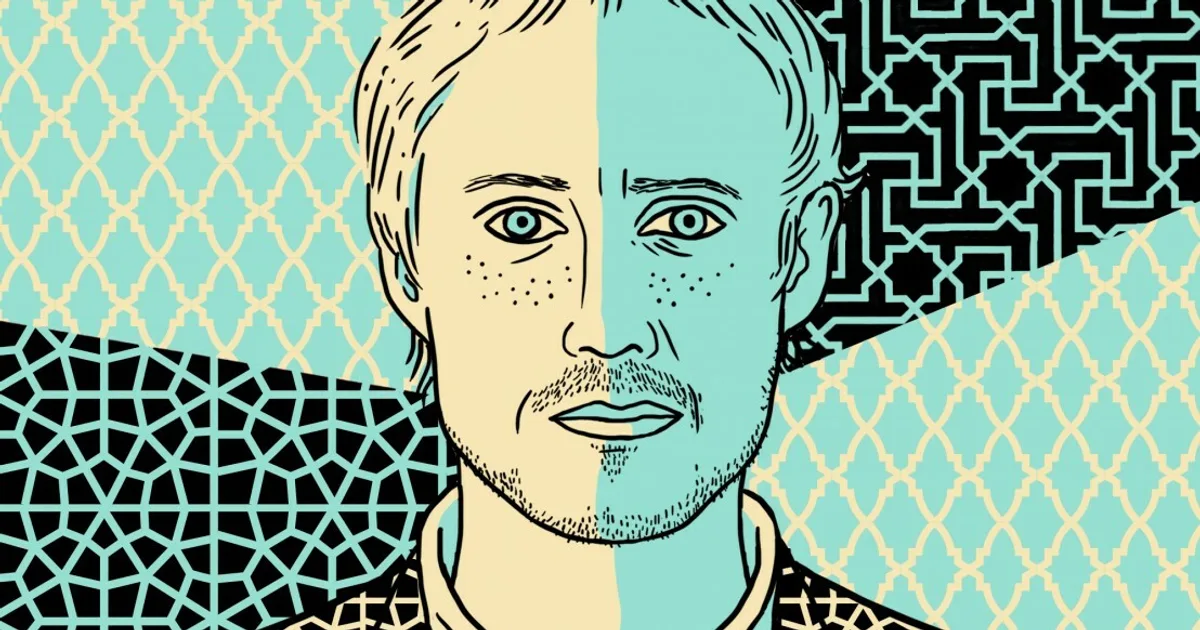

The Academy Awards may be a glitzy party with an arbitrary approach to dishing out Oscars but, within the circus, are moments of gravitas. László Nemes is the embodiment of gravitas. His debut feature, Son of Saul, is a relentless immersion in the quest of a Jewish prisoner whose job, in 1944, is to clear Auschwitz’s gas chambers of the dead.

Bodies – out of focus, naked and stacked high – are in Saul’s peripheral vision. This creates grief and empathy for a character who searches for reprise, despite the nightmarish horror all around. Seeing Nemes with his baby face and bullshit-free speech collecting the shiny Best Foreign Film gong is a positive omen for the future of this impressively serious Hungarian 39-year-old.

Get more Little White Lies

LWLies: How did you recreate the conditions of the extermination camps?

Nemes: The film takes place in and around one of the crematoriums of Auschwitz, so we found the right location and building. It had all the levels of the crematorium, from the attic to the ovens level to the lower levels – the underground undressing room and gas chamber, outside the court of the crematorium and the outside. Everything was in one place so you could have a continuous experience filming between the one level and the next.

And all the piles of bodies that you see in the background?

I’m not going to comment on that. This is the secret of the workshop. I know how we did it but it has to remain a sacred thing when we’re talking about the dead. I don’t want to disclose too much about that.

What are your thoughts on creative independence? Do you strive for it? If so, how?

It’s scary how little we are allowed, as filmmakers, to have our own worlds created because of people who want to second guess the market but actually don’t know more about the market than we do. They try to say we should make this film so it looks like another film, which already had success. But filmmaking is about taking risks. If a filmmaker doesn’t take risks then cinema is dying. You can see how a sort of very static mindset has taken over European filmmaking and worldwide filmmaking.

So how did you do it?

Just stick to your ambition, then you wait until you get lucky and hope that the project doesn’t die within you. I think I got lucky. When I was close to not realising it – actually not making this film happen – the Hungarian Film Fund was the only organisation willing to support this film. Had they not done this, it would have been impossible to do this film.

Did you come close to crying or did you cry at any point?

No. Inside, yes, I still am.

How close is the finished film to the vision you had before you made it?

Sixty per cent. I only think of the 40 per cent missing. I never think of the 60 per cent that I made happen.

What was your full ambition?

To have it the same but better.

Would that have been a technical change?

No, not technical. I’m the only one who knows but it just frustrates me. It’s not really an emotional change, it’s not the approach. It’s more the scope of it.

And that still haunts you?

Of course, that’s why I can’t watch the film, but I think in two years it’s going to be easier for me to watch it.

Did you make Son of Saul because it was an issue you were obsessed with?

Yeah.

Has making this film changed the nature of your obsession?

Yeah, it makes it a little bit easier to live with the thought of… I tried to communicate something that I had an intuition of, the experience of being a human in the midst of the extermination machine – something that hasn’t been communicated in cinema, the visceral experience of it. Not the external point of view, not the survival point of view, but something immersed in the reality of one human being with the limitations, the impossibility of knowing what’s going to happen. I wanted the imagination of the audience to recreate the experience of the camp.

Did you always… because I read that some of your family members…

People were killed in my family. It was not unusual for Jews to be killed. But it’s a very traumatic experience and I think it’s transmitted from generation to generation, in an almost genetic way. I wanted to make a film about that because people tend to consider the concentration camp as either something remote and abstract or historical, not really taking place here and now. Or in a very over-aestheticised fashion. I wanted to make it harder for other people to make films in the camp because it’s so easy to go there but it should be very hard to go there. You have to have the responsibility as a filmmaker to go there and talk about it. I wanted to bring the present of it, the here and now, and not this remote point of view.

Have your family seen the film?

My mother, my aunt, a few people. I made this for people who died in my family who have no trace of their existence apart from a few pictures. So many people died in terrible ways and they tried to erase even the fact that they existed by not even scattering their ashes. There’s something very… the destruction of people is something very… I’m very obsessed by it.

What’s next for you?

I have a project that takes place before the First World war; it’s the story of a young women in Budapest.

Have you written the script?

We have a script but it’s being rewritten and we are already working the preparation of the film.

Does this symbolise that you’re moving on from…

Yeah, I have to leave the subject. I don’t want to live in a crematorium forever.

Son of Saul is released 29 April.