Rather than a triumphant replay of the old hits, Jurassic World: Rebirth is a bit more like Malibu Stacy with a new hat. It’s a repackaged product with a couple of superficial bells and whistles that its makers believe audiences will want to see purely to remain in the loop with all the dino-based shenanigans.

Its numerous flagged/underscored/exclamation-pointed call-backs to the ’90s originals work double duty as balmy-eyed nostalgia and a tragic reminder that this is a franchise that hasn’t been able to whisk up an original thought since the credits rolled on the Steven Spielberg’s OG mega hit over three decades ago. And you know things are bad when you’re watching a summer blockbuster that’s part of the vaunted Jurassic Park IP and thinking, “Ho hum… I wonder what’s going on over at Skull Island right now…”.

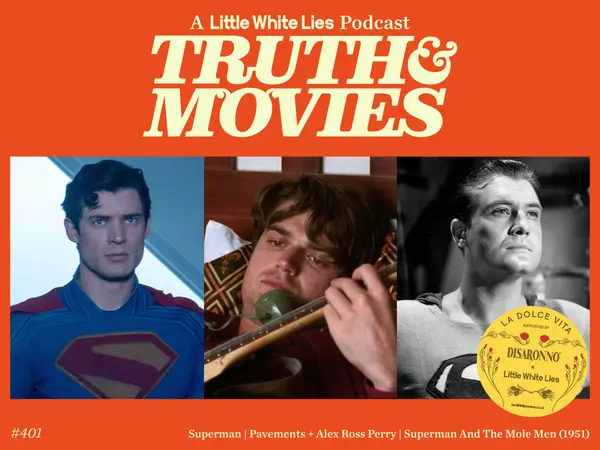

Get more Little White Lies

Veteran screenwriter David Koepp, who penned the first sequel, Jurassic Park: The Lost World, in 1997, returns to the DNA-splicing fray, and this new film feels every bit the rejected proposal from those salad days, a script whose dog-eared pages have been salvaged from the filing cabinet/waste bin of his old office. Often bracingly generic in its characterisations, its deployment of exposition and the occasional slow beat where someone will idly reminisce about the past, it’s baffling that someone who has worked on all varieties of film and at every level in the industry could deliver something so utterly devoid of interest or originality.

Aside from its shoddy conceit, it’s a script that does the dirty on its cast, in particular Mahershala Ali as the mercenary-for-hire Duncan who is given the remit to be recklessly impulsive when it’s revealed that he’s suffering from deep family-based trauma. Scarlett Johansson, meanwhile, has a nice line in cocky smirking as covert opps maestro Zora. She’s given the absolute non-dillemma of whether she’ll toe the corporate line as strictly set out by linen-suited weasel Krebs (Rupert Friend*), or score the winning goal for global morality and heed the wisdom of dashing palaeontologist Dr Loomis (Jonathan Bailey).

The plan here is that Krebs has offered Zora silly money to capture blood and tissue samples from three live dinosaurs employing technology created by Loomis. The snag is that their targets – representing land, sea and air – all now thrive in a tropical microclimate along the equator that also happens to be the island that was used as a testing ground for dinosaur cross-breeding. We all know it’s not going to be the quick “pop in, pop out” escapade that they all think it will be, and our gang also have to deal with the mightily naffed off “D‑Rex”, which is exactly like if a T‑Rex had been smashed in the face with the world’s largest frying pan.

The film struggles to find a justification for its existence, and we’re told that the world has grown weary of the spectacle of dinosaurs. Which in itself is a completely cynical assumption in line with saying, say, that humanity will one day grow tired and yearn for the extinction of panthers. Krebs and his deep-pocketed paymasters believe that this flashpoint of collective apathy is the time to make their play and do a little bit of under-the-radar dinosaur vivisection in order to produce a cure for heart disease, which they can charge a small fortune for once they have the patent.

The “human interest” element to the story is bolted on in the form of superdad Reuben (Manuel Garcia-Rulfo) and his two daughters (Audrina Miranda as pre-teen Isabella and Luna Blaise as late-teen Teresa) and Teresa’s charming slacker boyfriend Xavier (David Iacono) as they heedlessly attempt to sail through dino infested waters in the name of family adventure. And this is two minutes after being told repeatedly that this area is a human no-go zone as death will likely be imminent. So sympathy levels are a tad hard to come by, even if the level of performance and character depth is a little bit higher/deeper on this side of the playing field.

What saves the film from the summer doldrums is the typically stellar work by director Gareth Edwards, who, despite the quality of the materials he’s been given to work with, proves once more that he’s one of the most interesting and original artists in Hollywood when it comes to creating CG set pieces. There’s one sequence at the film’s mid-point that pushes the technology to satisfying extremes by having digital dinosaurs intersecting with human characters while being flung down some river rapids.

Edwards’s involvement was the one thing keeping the candle aflame in terms of our hopes that this moribund, never-ending franchise might have turned a corner. Yet even working at full pelt, there’s just too much that’s wrong and silly and derivative about this tired, tired run-out. The actors are competent; there are a few tasty zingers; the effects are seamless. But the whole enterprise just feels like the same thing we’ve seen over and over again, and that the addition of a “new hat” has been deemed more of an irritant than a gift to create something fresh.

*I’d like to make readers aware of a pertinent comment that was made on the LWLies private group chat by my esteemed colleague Hannah Strong, who noted that, “He was v much Rupert Foe in JW”. It felt right to include the observation in this, our official review of the film. Thanks.